Blaise Pascal (1623 – 1662) is a personal hero of mine. Over the years, I’ve had a few “good” ideas that I thought were original, only to find out later that Pascal wrote them down more eloquently 350 years ago. I could’ve listed 50 things that I love about Pascal, but I’ve narrowed it down to 5. And yes, Karlie and I named our son Blaise not only because it’s a cool name, but because he was a pretty cool guy.

1. His ingenuity. Pascal invented the first computer (a mechanical calculator that used binary code), the hydraulic press, the syringe, modern journalism, the first public transportation system (a horse-and-carriage system for Paris), the vacuum cleaner, and the one-wheeled wheelbarrow. In addition, he was a forerunner of integral calculus and a co-founder of probability theory. There’s a ton of stuff named after him—Pascal’s Triangle, Pascal’s Law, Pascal’s Wager, Pascal’s Theorem, units of pressure are abbreviated Pa (for Pascal), and there are computer programming languages named after him. He did all of this despite poor health and a short life—he died at 39. After his death, his sister found hundreds of written fragments of Pascal’s thoughts (pensées in French) that were later collected and published.

2. He identified the human predicament: there’s something missing in our hearts—we all have an insatiable longing for transcendence.

“What else does this craving proclaim but that there was once in man a true state of happiness, of which all that now remains is the empty print and trace? This he tries in vain to fill with everything around him though none can help, since this infinite abyss can be filled only with an infinite and immutable object, in other words by God himself.” – Pensée 148

In other words, we all have an insatiable longing for happiness, love, aesthetics, meaning, and purpose that nothing under the sun can satisfy. We try to fill this gap with diversions, temporary pleasures, and escapisms. What is this abyss we all feel? According to C. S. Lewis, we feel hunger because there’s such a thing as food; and we feel sexual desire because there’s such a thing as sex. Lewis concludes, “If I find in myself a desire which no experience in this world can satisfy, the most probable explanation is that I was made for another world." Pascal reasoned that God was the only thing that could fill the abyss in our hearts.

3. Pascal wanted people to be seekers and lovers of truth. But he also realized the temptations for truth to be twisted and distorted to meet our selfish desires. Here, Pascal plays the prophet, forecasting the fake news / post-truth invasion of modern times.

“Truth is so obscured nowadays and lies [are] so well established that unless we love the truth we shall never recognize it.” – Pensée 739

For Pascal, the truest or clearest picture of the world must explain the human condition and our peculiar proclivity to be both wretched and great. Pascal felt that Christianity, with love as its central tenant, was both too profound to plumb its depths yet could also be understood by children. Jesus is the perfect completion for everything we lack and desire. “In [Christ] is all our virtue and all our happiness” (Pensée 416).

Pascal came to know the truth of Jesus Christ through various ways, most supremely through a personal experience that affected him so greatly that he stitched his short reflection of that experience (Pensée 913) in to the lining of his coat pocket so it would always be by his side.

4. He provided insights into an old mystery: the hiddenness of God. Pascal reasoned that God wishes “to appear only to those who seek him with all their heart and hidden from those who shun him with all their heart” (Pensée 149). Pascal said that to know God, one must have a heart of humility and an earnestness to seek him. But if you wish to keep God hidden, allow your pride to flourish. In the end, Pascal felt there was enough light to find God for those seekers focused on the things of God instead of the treasures of this world. To paraphrase Pascal, God has given evidence sufficiently clear for those with an open heart, but sufficiently vague so as not to compel those whose hearts are closed.

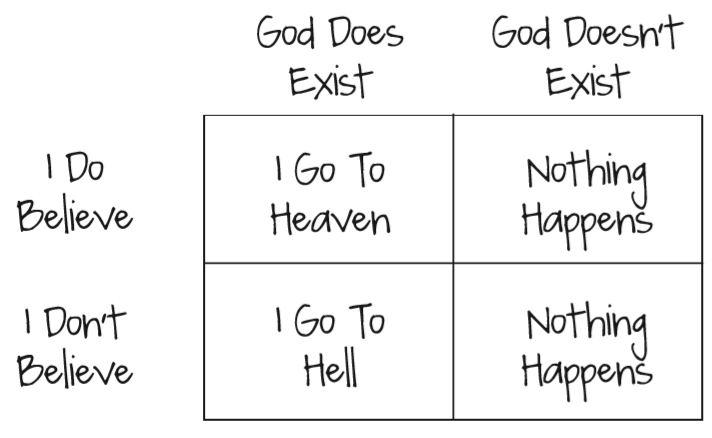

5. Pascal’s Wager. Pascal recognized that we all have a free choice to accept or reject God but felt that a clearer illustration of the options, called Pascal’s Wager, would help reveal the potential payoffs, such that a logical decision could be made.

The wager assumes that everyone must decide whether God exists or not. You can’t bow out of this decision. If you put your faith in God’s existence and, after death, find that He does exist, then the eternal joy of heaven awaits you. If God does not exist, then nothing happens after death, and you’ve lost nothing. Alternatively, if you live your life believing there is no God and, after death, find that He does exist, then you will endure infinite loss—an eternity in hell separated from God’s goodness. If God does not exist, then nothing happens after death, and you’ve gained nothing. Pascal argued that since choosing God maximizes happiness, it is the only prudent choice.

Pascal’s Wager always resonated with me, partly because I pursued a career in finance and saw the intrinsic value of options. When I was 17, I learned about stock options and spent my summer break day trading option contracts. In my view—and to use an investing term—the “smart money” is on Jesus Christ. As C. S. Lewis remarked, “Christianity is a statement which, if false, is of no importance, and, if true, is of infinite importance. The one thing it cannot be is moderately important.” The emphasis, for both Lewis and Pascal, is that humans are betting with their lives.

The Wager is perhaps best suited for those who are on the fence—those who think the evidence for God’s existence is 50/50. But Pascal did not think the odds were 50/50. He wrote at great lengths about the evidence for the historicity of the Christian faith, the rationale for God’s existence, the trustworthiness of the Bible, and the uniqueness of Christianity’s diagnosis and remedy of humanity’s problems.

Pascal played an important role in my conversion to Christianity by helping me see the darkness of the human predicament without God, the temptations of apathy and distraction that diverted me away from God, and the value of an infinite payout—eternity in heaven. I’ll leave you with one more masterstroke from Pascal’s pen:

“Do small things as if they were great, because of the majesty of Christ, who does them in us and lives our life, and great things as if they were small and easy, because of his almighty power.” – Pensée 919