The audiobook for Trading Gods is now available!

For audiobook listeners, the following images were part of the physical book.

Rembrandt painting from Chapter 4: Science and Evidence.

Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606-1669), Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633. Oil on canvas, 160 x 128 cm (63 x 50 3/8 in.). Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (P21s24).

In Rembrandt’s only seascape painting, The Storm on the Sea in Galilee, the apostles are in the boat with Jesus, crossing the Sea of Galilee, as recounted in Mark 4. A violent storm has the boat near destruction, and the apostles scramble to wake Jesus, who rescues them by quieting the storm. A purely scientific approach to the painting would involve an analysis of the pigments in the paint, the canvas structure, the mathematical symmetry, and the type of brush. But science can’t tell you if the painting is beautiful or inspiring.

Science can tell you there are 14 people in the boat, but it can’t explain why there’s a fourteenth person when only 13 should be present (Jesus plus the 12 apostles). The fourteenth person in the boat is Rembrandt, who put himself into the painting. Rembrandt felt that to really grasp the significance of the salvation story, you must be in the boat—in complete desperation for your life—not observing from the safety of the shore. Ultimately, the painting is more beautiful and meaningful through multiple ways of knowing.

The two spectrums of knowing are discussed in Chapter 5: Faith and Knowledge.

We have absolute certainty with indisputable evidence about so few things in life. Everything relating to human affairs, everything complex, and everything that really matters in life is not known with absolute certainty. Instead, the way we live our lives is using probable knowledge.

The idea of faith is similar to the idea of probable knowledge. Notice how the line of faith does not extend to the length of absolute knowledge. That difference is important. The arrow to the right represents faith that something is true, while the left arrow represents faith that something is not true. In either case, we don’t have absolute knowledge with indisputable evidence. Faith involves trusting in someone or something because you think it’s true based on the available evidence

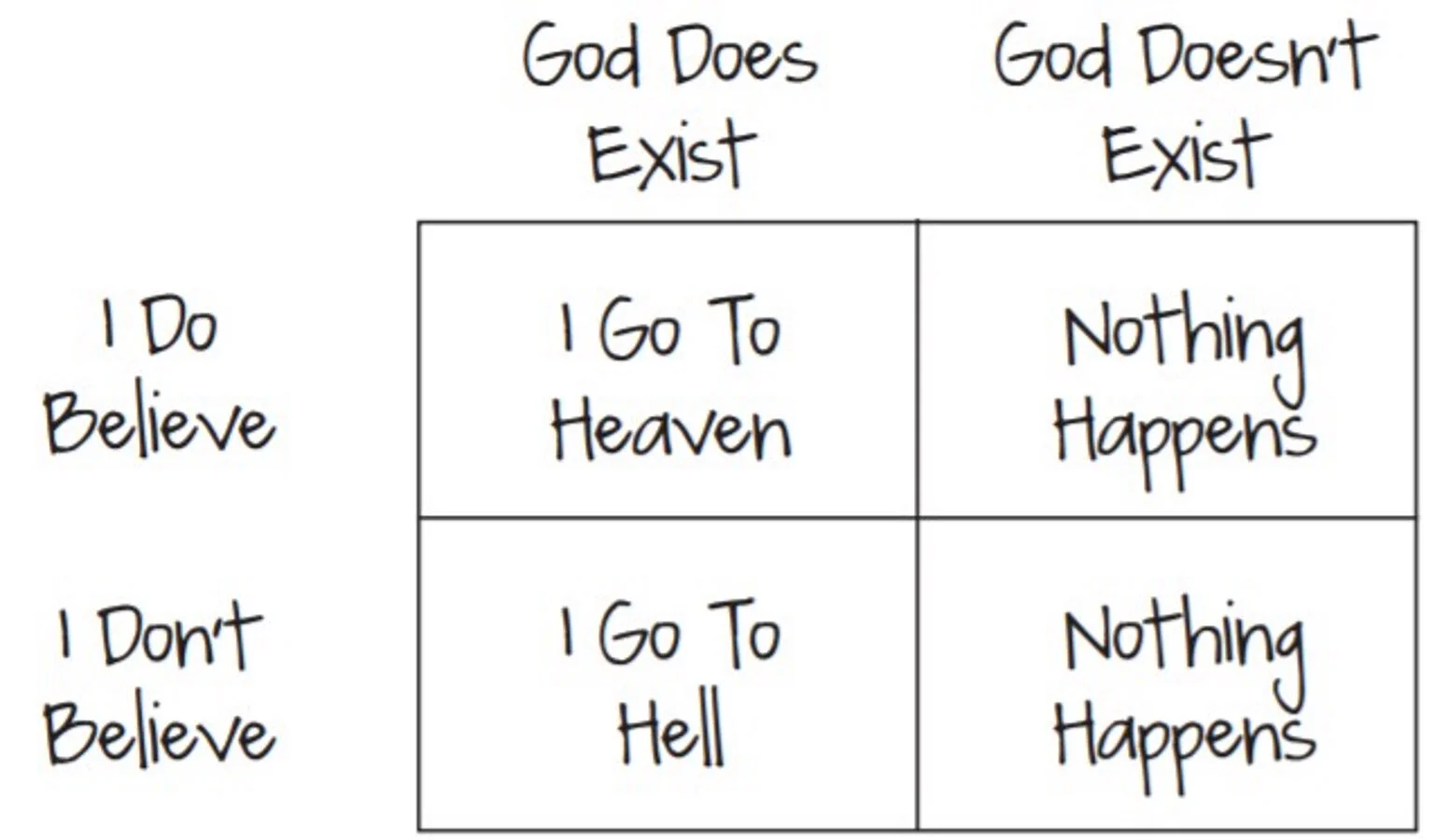

Pascal’s Wager (discussed in Chapter 6: Freedom and Choice)

The wager assumes that everyone must decide whether God exists or not. You can’t bow out of this decision. If you put your faith in God’s existence and, after death, find that he does exist, then the eternal joy of heaven awaits you. If God does not exist, then nothing happens after death, and you’ve lost nothing. Alternatively, if you live your life believing there is no God and, after death, find that he does exist, then you will endure infinite loss—an eternity in hell separated from God’s goodness. If God does not exist, then nothing happens after death, and you’ve gained nothing. Pascal argued that since choosing God maximizes happiness, it is the only prudent choice.